Jamie Hargreaves

Welcome to my blog.

I've Been to Hell and It Looks Like a Jupyter Notebook

by Jamie Hargreaves

- Data engineering in notebook hell

- Stop writing scripts, start writing applications

- Structuring a typical project

- Defining the application boundaries

- Structuring a job

- Abstracting I/O components

- Enforcing SQL-based transforms

- Orchestrating individual ETL processes

- Wrapping up

Data engineering in notebook hell

One of my biggest frustrations with data engineering as a discipline (and enterprise data platforms like Databricks and Microsoft Fabric), is the relentless and seemingly never-ending push towards notebooks as the primary mechanism to write and deliver code. For me, notebooks are synonymous with a scripting style approach to development that lends itself to a host of bad practices, but if they’re so obviously bad, why have they become so popular and why do platforms seem so intent on encouraging their use? Several reasons come to mind:

-

Time-to-value: notebooks take us from zero to something quickly, they let us write code and interact with data with little to no setup, often inside the browser.

-

Versatility: notebooks let us flit between multiple languages like Python, SQL and Java effortlessly, and even allow us to embed documentation with inline Markdown.

-

Accessibility: notebooks are used across disciplines, making them a familiar tool for data engineers, data scientists and data analysts, lowering the barrier to entry for less technical users and abstracting away complexities like environment and dependency management.

-

Collaboration: platforms like Databricks offer collaborative notebook experiences, similar to a shared Google doc, meaning multiple team members can write and interact with code simultaneously.

In an agile environment where we want to get data into the hands of our users as quickly as possible, things like time-to-value and ease of use are nothing to scoff at. As is often the case though, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch”, and these benefits typically come with some significant tradeoffs:

-

Developer experience: since most platforms offer a browser-based notebook interface, the physical act of writing code can be sluggish and frustrating. In addition, the ease of use tends to come at the expense of a feature-incomplete experience, where debugging is hard or impossible and basic IDE configuration is non-existent.

-

Code structure: notebooks have historically been geared towards activities like exploratory data analysis or prototyping. Modularising code into re-usable interfaces and components can be difficult, especially in monorepos where path configuration can become messy. We’re often forced to resort to things like magic

%runcommands and hard-coded relative paths, where “importing” becomes slang for eager execution, and namespace conflicts become a risk. -

Deployability: we have no real way of turning notebooks into deployable, versioned artifacts. Whereas we might build a Python package into a wheel and promote it through environments, we’re often left with little more than a glorified copy and paste deployment pipeline when dealing with notebooks.

-

Code quality: notebooks are nearly impossible to run through standard code quality checks. Since standard import approaches often don’t work - and in some cases the code itself is stored in formats like JSON - applying linting, formatting, type checking and security scanning is often impossible or, at best, overly convoluted and bespoke.

-

Testability: since the use of notebooks often brings with it a “scripting” mentality to development, we routinely end up with code which is poorly abstracted and difficult to test. When testing is possible, it’s almost always difficult to automate, since notebooks couple us tightly to a given development platform, rather than an environment which can be easily replicated in continuous integration pipelines.

Stop writing scripts, start writing applications

To embrace the “stop writing scripts, start writing applications” mantra means a fundamental shift in how we think about our code. We move from a focus on isolated, script-first notebooks to a focus on well-reasoned, well-abstracted and well-tested data applications. In doing this, we should adopt proven software engineering best practices built up over decades of delivery. Data engineering is, after all, a specialised branch of software engineering focused on systems that collect, process, and store data. The same principles that drive successful software delivery apply equally to successful data delivery.

Structuring a typical project

In general, a data application should be aligned with a data domain, data product, or some other well-defined boundary. In practice, a data application will typically take the form of a series of jobs. We want to aim for individual jobs to be independent in terms of physical execution and manage logical dependencies through an orchestration process, rather than embedding them in the application itself. For example, when populating a fact in a star schema, the dimensions must be loaded first since the fact depends on their foreign keys. Each dimension and the fact would be defined as independent jobs, with orchestration ensuring the fact runs only after the dimensions. That dependency might be enforced directly - waiting for the upstream jobs to complete - or indirectly, by checking “freshness” metadata on the dimension tables.

To make the rest of this discussion more concrete, we’re going to assume our data application is PySpark-based and focus on that context. To begin, we want to structure our project so that we’re able to build a versioned and deployable artifact, and make use of the full Python ecosystem. This really just means structuring the project as a standard Python package, using a tool like Poetry, and deploying it as a wheel (or similar artifact). From there, we can apply the same best practices expected of any modern Python project, namely:

- Linting and code formatting (e.g., Ruff)

- Static type checking (e.g., Mypy)

- Security scanning (e.g., Bandit)

- Docstring formatting (e.g., Docformatter)

- Automated API documentation (e.g., Pdoc)

- Unit and integration testing (e.g., Pytest)

- Architectural decision records (e.g., as outlined by Michael Nygard)

⚠️ A platform’s ability to deploy applications as wheels (rather than relying on notebooks) is a strong indicator of its maturity and suitability as a serious, scalable development environment.

In terms of a loose project structure, a typical, minimal project for the foo domain might look something like this:

├── config

├── docs

│ ├── api

│ └── decisions

├── src

│ └── foo

│ ├── jobs

│ └── tools

├── .gitignore

├── .pre-commit-config.yaml

├── pyproject.toml

└── README.md

Defining the application boundaries

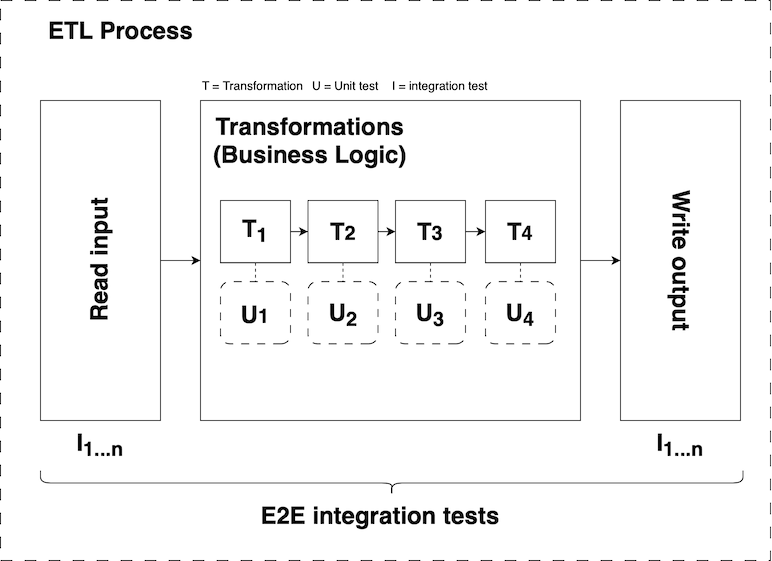

The term “data application” is purposefully vague but in reality these applications often take the form of an Extract, Transform, Load (ETL) process. If we think about the typical ETL process that we might want to build on platforms like Databricks or Amazon EMR, we can really think of the Extract and Load stages as defining the I/O boundaries of the application - it’s at these points that we reach out and interact with the world. This fact should inform the overall software design and, in particular, the way we test the different components of the process.

As outlined in the diagram above, each ETL process should follow the same generic structure where I/O boundaries are isolated from core transformations (i.e., the main business logic):

-

Reading and writing data should be abstracted into reusable interfaces that form a clear boundary between I/O and business logic. These interfaces should be easy to test, mock, and verify through both unit and integration tests.

-

The bulk of an ETL process should be made up of more or less pure transform functions which take one or more data inputs (along with any relevant parameters), and return a single data output.

-

For the sake of portability and accessibility, transforms should be written as SQL

SELECTstatements. -

Each transform should have an associated unit test.

-

Each ETL process should include end-to-end integration tests to verify that it runs correctly and produces the expected outputs for defined inputs.

Structuring a job

Using the foo domain example from above, each job within the domain should be constructed from two pieces:

src

└── foo

├── jobs

│ └── bar

│ ├── __init__.py

│ ├── etl.py

│ └── transforms.py

-

foo.jobs.bar.etl- forms the basis for ETL orchestration, defining arunfunction which reads data, applies transforms, and writes to the target. -

foo.jobs.bar.transforms- defines the transforms used in the ETL process.

From a testing perspective, etl is tested through integration tests and transforms is tested through unit tests.

Abstracting I/O components

A useful abstraction when trying to isolate the the I/O components of an ETL process is a Data Access Layer (DAL) which acts as a lightweight wrapper around read and write operations against a datastore. Let’s imagine that we’re reading from and writing to tables in a Unity Catalog metastore in Databricks - what might a simple DAL look like?

# src/foo/tools/stores/unity_catalog.py

from logging import Logger

from pyspark.sql import DataFrame, SparkSession

class UnityCatalogStore:

def __init__(self, spark: SparkSession, logger: Logger, catalog: str) -> None:

self._spark = spark

self._logger = logger

self._catalog = catalog

def read(self, table: str, schema: str, select: list[str] | None = None) -> DataFrame:

name = f"{schema}.{table}"

columns = ["*"] if select is None else select

self._logger.info(f"Reading table '{name}' from catalog '{self._catalog}'")

return self._spark.read.table(f"{self._catalog}.{name}").select(*columns)

def append(self, data: DataFrame, table: str, schema: str) -> None:

name = f"{schema}.{table}"

self._logger.info(f"Appending records to table '{name}' in catalog '{self._catalog}'")

data.write.format("delta").mode("append").saveAsTable(f"{self._catalog}.{name}")

We can create catalog-specific instances of the UnityCatalogStore class and use them to interact with data consistently across multiple ETL processes:

import logging

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from foo.tools.stores.unity_catalog import UnityCatalogStore

spark = SparkSession.builder.getOrCreate()

logger = logging.getLogger("example")

# Log output:

# [2025-08-13 16:19:52,900 | INFO ] : Reading table 'my_schema.my_table' from catalog 'my_catalog'

my_catalog = UnityCatalogStore(spark, logger, "my_catalog")

my_table = my_catalog.read("my_table", "my_schema")

When it comes to type hints, rather than specifying what datastore we’re interacting with (Unity Catalog, SQL Server, Amazon S3 etc.), we could instead specify how we interact with it:

# src/foo/tools/stores/behaviors.py

from typing import Protocol

from pyspark.sql import DataFrame

class HasRead(Protocol):

def read(self, table: str, schema: str, select: list[str] | None = None) -> DataFrame:

"""Reads a table from the given schema and returns the result as a DataFrame."""

class HasAppend(Protocol):

def append(self, data: DataFrame, table: str, schema: str) -> None:

"""Appends records from the source DataFrame to the target table."""

Now, we don’t really care where our data is stored, we just care that wherever it is, it can be interacted with in the ways we expect. Using Protocols like this is more informative than just knowing that, for example, “blah is a Unity Catalog catalog” - now we know that blah acts as a data source because we specify the need for it to support a read method. In addition, if blah were originally a SQL Server database but has now been migrated to Unity Catalog, nothing in the ETL code needs to change because all the code cares about is that the read behaviour is still supported. By modelling these behaviours as separate Protocol types we keep the contracts small and focused, and our orchestration logic stays completely agnostic about the actual implementation. The input DALs to our ETL process could be:

- Different concrete DALs for different systems

- Mock objects for testing

- Temporary stubs whilst migrating between storage systems

The orchestration code doesn’t care — it only cares that each object supports the behaviour it needs.

Enforcing SQL-based transforms

When we outlined our ETL principles we mentioned that transforms should be written in the form of SQL SELECT statements - this is ultimately down to personal preference but if we do want to enforce it, we can again implement a simple abstraction:

# src/foo/tools/query_engine.py

from typing import Any

from pyspark.sql import DataFrame, SparkSession

class SparkQueryEngine:

def __init__(self, spark: SparkSession) -> None:

self._spark = spark

def query(

self, statement: str, tables: dict[str, DataFrame], params: dict[str, Any] | None = None

) -> DataFrame:

return self._spark.sql(sqlQuery=statement, args=params, **tables)

This class looks fairly unassuming but it allows us to avoid passing around a loose Spark session and instead lets us pass around an interface that enforces an agreed approach to defining transforms. Now, we can define transforms directly in SQL:

# src/foo/jobs/bar/transforms.py

from pyspark.sql import DataFrame

from foo.tools.query_engine import SparkQueryEngine

def add_customer_name(

engine: SparkQueryEngine, orders: DataFrame, customers: DataFrame, region: str

) -> DataFrame:

return engine.query(

statement="""

SELECT

o.id,

o.amount,

c.name AS customer_name

FROM

{orders} o

INNER JOIN

{customers} c

ON o.customer_id = c.id AND o.region = :region

""",

tables={"orders": orders, "customers": customers},

params={"region": region},

)

The benefit of running SparkSQL queries directly on top of DataFrames as above is that we no longer need to worry about setting up temporary views for each of our DataFrames, and we can easily unit test these SQL-based transforms:

# src/tests/unit/jobs/bar/test_transforms.py

import pytest

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from pyspark.testing import assertDataFrameEqual

from foo.jobs.bar import transforms

from foo.tools.query_engine import SparkQueryEngine

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def spark() -> SparkSession:

return SparkSession.builder.master("local[1]").getOrCreate()

@pytest.fixture(scope="session")

def engine(spark: SparkSession) -> SparkQueryEngine:

return SparkQueryEngine(spark)

def test_should_add_customer_name(spark: SparkSession, engine: SparkQueryEngine) -> None:

orders = spark.createDataFrame(

data=[(1, 1, 100.0, "EU"), (2, 2, 200.0, "EU"), (3, 3, 300.0, "US")],

schema="id BIGINT, customer_id BIGINT, amount DOUBLE, region STRING",

)

customers = spark.createDataFrame(

data=[(1, "Alice"), (2, "Bob"), (3, "Charlie"), (4, "Diana")],

schema="id BIGINT, name STRING",

)

expected = spark.createDataFrame(

data=[(1, 100.0, "Alice"), (2, 200.0, "Bob")],

schema="id BIGINT, amount DOUBLE, customer_name STRING",

)

actual = transforms.add_customer_name(engine, orders, customers, region="EU")

assertDataFrameEqual(actual, expected)

This approach to building ETL processes works particularly well with a RED-GREEN-REFACTOR workflow. Since the read and write operations are usually already implemented, we can focus on defining the necessary transformations. For each transformation, we first write a test specifying the expected output, then implement the transform to pass the test, and finally refine and optimize the logic.

Orchestrating individual ETL processes

Using the ideas we’ve outlined above, the foo domain’s bar job would implement an etl orchestration module that looks something like this:

# src/foo/jobs/bar/etl.py

from logging import Logger

from foo.jobs.bar import transforms

from foo.tools.query_engine import SparkQueryEngine

from foo.tools.stores.behaviors import HasAppend, HasRead

def run(

sales_store: HasRead,

customer_store: HasRead,

curated_store: HasAppend,

engine: SparkQueryEngine,

) -> None:

# Extract

orders = sales_store.read("order", "sales")

customers = customer_store.read("customer", "masterdata")

# Transform

transformed = transforms.add_customer_name(engine, orders, customers, region="EU")

transformed = transforms.aggregate_order_amount_by_customer(engine, transformed)

# Load

curated_store.append(transformed, "order_aggregation", "sales")

This approach ensures that:

- Each job is isolated, with dependencies only on the data it reads and the existence of the target it writes to.

- Core business rules in the transforms are testable in isolation and written in a format accessible to users beyond data engineers.

- The overall ETL process is easily testable, either by using real table instances or mocking the DALs passed to the

runfunction. - Each stage is clearly separated, providing a straightforward, high-level view of data flow through the ETL process.

Depending on the similarity of jobs in the foo domain, we can define a single entrypoint for the application or one per job. The entrypoint handles instantiating the Spark session and DALs (and anything else we want to pass into the run function). We might also use a decorator to auto-log key execution metrics or to catch, log and re-raise unhandled exceptions, keeping the run function uncluttered.

Wrapping up

Notebooks are powerful for exploration and prototyping, but as our data systems grow in complexity, they become a barrier to maintainability, testability, and scalability. By treating each data domain as a well-defined application, structuring ETL processes with clear I/O boundaries, and enforcing testable, SQL-based transformations, we can build data applications that are reliable, reusable, and easier to operate.

Adopting these practices brings the benefits of software engineering to data engineering: modularity, clear dependencies, automated testing, and the ability to deploy versioned artifacts. Teams that invest in these patterns are better positioned to scale their data infrastructure, reduce technical debt, and deliver consistent value to their users.

tags: python - spark - etl