Jamie Hargreaves

Welcome to my blog.

Pragmatic Functional Programming

by Jamie Hargreaves

Who cares?

Before we get into any of the details of functional programming (FP), let’s clear up the most important question: who cares? When I’m writing code, I want it to satisfy two main requirements:

- Easy to read and understand

- Easy to test

If a programming paradigm can’t help with these requirements, then I’m not interested. Luckily, I think FP can help achieve both.

That’s great, but why another blog? The main reason is that I found myself constantly struggling to learn about FP in the context of Python (which is the language I write in day-to-day). The purpose of this post is to frame what I’ve learnt about FP so far in the context of Python and, hopefully, save other people from the drudgery of having to piece together a convoluted tapestry of blogs, conference talks, books and StackOverflow threads (at least for the basics).

What makes code functional?

I’ve decreed that FP can somehow help you write better code, but what exactly makes code functional in the first place? When I started learning about FP, the answer to that question was surprisingly elusive. After a while, I stumbled upon a really nice blog by Mary Rose Cook called An introduction to functional programming. In the blog, Mary hits home the fact that functional code is just code without side-effects. This fact is something that’s often missing from a lot of explanations of FP. What typically overshadows it is a discussion about writing declarative code. Lots of people will tell you about the benefits of using map, reduce and filter, tail call optimistion, folding, currying and so on. Whilst I’m a massive proponent of writing declarative code, none of these things inherently make code functional. I usually think about FP as follows:

Functional programming is about building functionality through the composition of pure functions.

Function composition

When we talk about function composition, all we’re really talking about is directly passing the return value from one function as the argument to another function without defining any intermediary variables. Let’s imagine we have three functions f, g and h, and some variable x. If we want to pass the result of evaluating f(x) as the argument to g and pass that result as the argument to h, then we could do that easily:

f_result = f(x)

g_result = g(f_result)

h_result = h(g_result)

Alternatively, we could cut out the middle man and do the whole thing in a one-line operation:

h_result = h(g(f(x)))

This exactly what we’re thinking of when we talk about function composition. The obvious downside here is that this is really ugly, especially with more functions (all of which have proper names), so later in the series we’ll look at more aesthetic (and practical) ways to perform this kind of operation.

Functional purity

Okay, so we understand the first part of the FP definition, but we still have the second part: what exactly is a pure function? A pure function is any function which:

- Is referentially transparent, and

- Has no side effects

Both of these things are very “FP buzzword” and their meanings aren’t particularly obvious but they’re both terms that get thrown around a lot. Simply, a function is referentially transparent if replacing the function with its result doesn’t change the behaviour of the application. A function has no side-effects if it doesn’t rely on or alter anything outside of its local scope.

As I mentioned, the whole purpose of this blog series is to talk about FP in the context of Python, so let’s look at an example of a pure Python function:

# ✨ Pure ✨

# ✅ Referentially transparent

# ✅ No side-effects

def pure_add(a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

The aptly-named function above takes two integers and returns their sum. Based on the criteria I gave above, the function adheres to the definition of purity. An impure version of the function might look as follows:

# 🤮 Impure 🤮

# ❌ Referentially transparent

# ❌ No side-effects

def impure_add(a: int, b: int) -> int:

print(f"Adding {a} and {b}.")

return a + b

This function is impure because it fails against both the criteria we set. Firstly, it isn’t referentially transparent because, whilst the same input evaluates to the same result, we couldn’t replace calls to the function with that result whilst maintaining the same application behaviour. Namely, if we just substituted the value 3 everywhere we saw impure_add(1, 2), then the application wouldn’t be the same because we’d no longer print anything to the console. Secondly, the act of printing is itself a side-effect because it’s an I/O operation; it reaches out and communicates with the outside world, affecting something outside the scope of the function.

The practical implications of functional purity were quite surprising to me. If we can’t do something as simple as print to the console in a pure function, then what else can’t we do? Well, in a truly pure function (and this is by no means an exhaustive list), we can’t:

- Log

- Interact with files, databases or REST APIs

- Generate random numbers

- Raise exceptions

At this point you’d be sensible to question what exactly the point of a pure function is if they can’t really do anything. An important point to keep in mind is that a lot of the things we’d want to do in a function that would introduce impurity (at least in the context of data engineering), are typically I/O operations. The problem is that code without side-effects doesn’t do anything useful. At the bare minimum if, as a data engineer, I can’t read or write data, then I can’t do my job.

If we think about where the impurity in a typical data pipeline lies, it’s mostly confined to the “edges” since those are the places where we need to perform I/O to read and write data. When we’re doing the bulk of our work (i.e., when we’re actually transforming data), our functions will generally take some data in and apply a series of functions to that data which produce a predictable result. Does that mean our functions will always be pure though? No. It’s certainly the case that a lot of our functions are likely to be pure, but at a minimum, we’re going to want some level of exception handling and logging.

We’re saying then that despite our best intentions, impurity in our functions is pretty much unavoidable, but we’re also saying that FP is all about composing pure functions, so what gives? In functional languages (like Haskell, F#, Scala etc.), the usual solution is to use something called a Monad, so let’s dive into what exactly they are along with their lesser-known friends, Functors and Applicatives.

Functors

Monads are probably the most off-putting concept in FP, or at least they were for me. Despite how complicated they can seem at first, I don’t think “being complicated” is the reason that Monads are so off-putting, I think it’s because they’re almost universally explained in the context of Haskell.

I won’t go too deep on Haskell here (would that I could), but the TL;DR is that Haskell is a popular, purely functional programming language. This means that (unlike Python), Haskell is quite specific about how it expects code to be written and doesn’t let you just mix and match your paradigms any which way you please. The reason this matters to people like us is that a good chunk of FP resources are framed in the context of Haskell which can make learning about FP a real grind in the early stages (though if you are interested, there’s probably no better place to start than Learn You a Haskell for Great Good).

To talk about Monads we need to first talk about Functors and Applicatives. This is the first place that really tripped me up when I started learning about FP because most intros start from Monads and skip Functors and Applicatives entirely which can cause a lot of confusion when it comes to understanding and using Monads in practice (at least in my experience). The best explanation I’ve found on the topic is a blog by Adit Bhargava entitled Functors, Applicatives and Monads in Pictures. I don’t necessarily think there’s a lot I can add on top of this blog in terms of the fundamentals but what I can do is to re-frame things in the context of Python and provide some practical examples.

Exceptions in pure functions

You’ll recall that previously one of the things in my list of “useful things that pure functions can’t do” was exception handling. An example of why (in the context of data engineering), is a function which takes a dataframe, applies some transformations and returns a new dataframe. If we had a try/except block in the function that (magically) caught out of memory exceptions and returned some default dataframe whenever one occurred (however implausible), then we could imagine a situation where the hardware configuration of the system could alter the value the function returns; a single-node cluster might return one dataframe whilst a large, multi-node cluster might return another. A function like that clearly wouldn’t be referentially transparent since it wouldn’t produce a deterministic result.

That’s handling exceptions, but what about throwing exceptions, is that a problem? The answer is a distinctly dissatisfying…🤷♀️. I’ve honestly never found anything particularly clear on this either way. In general though, we tend to avoid throwing exceptions in FP because we have alternate ways to work with them.

Encoding exceptions with Functors

One functional alternative to throwing exceptions is to use a Functor called Either. You can think of a Functor as way to encode some kind of behaviour associated with a value (in this case, the occurrence of an exception). The Either Functor is a bit like a class with two sub-classes, Left and Right, which encode failure and success, respectively.

Let’s think about a simple example of a function which raises an exception given a bad input:

def divide(a: float, b: float) -> float:

return a / b

When the value of b is zero, rather than returning, the function raises a ZeroDivisionError. Since the cause of the exception is wholly deterministic, we can use the PyMonad implementation of Either to re-write this function in a way that avoids the exception entirely:

from pymonad.either import Either, Left, Right

def divide(a: float, b: float) -> Either[ZeroDivisionError, float]:

return Left(ZeroDivisionError) if b == 0 else Right(a / b)

Unlike the previous version, the new version of our function always returns a predictable result of type Either[ZeroDivisionError, float] - it encodes the occurrence of an exception without actually raising one and crashing the program.

Pure functions tell us about the good days and the bad days

Whilst the purity of throwing exceptions seems up for debate, there’s actually an arguably better reason (IMO) to avoid it, one which is wonderfully elucidated in the Pure Function Signatures Tell All chapter of the fantastic book Functional Programming Simplified by Alvin Alexander. The crux of it is that our original function didn’t give us any indication that it might raise an exception, it told us that it takes two floats and returns a float, but that isn’t always true. Whilst for a simple function like our original divide we can easily look at the implementation and deduce when an exception would be raised, that’s not always going to be the case with most functions we encounter. On the other hand, our new “Functorised” version of divide is totally honest; it tells use about the good days and the bad days - when things go well, it returns a float, when they don’t, it returns a ZeroDivisionError.

I have this dream where I’m trapped in a Functor and I can’t get out

How do we actually get values out of a Functor? Remember, if we call divide(1.0, 2.0), we don’t return 0.5, we return Right(0.5). In most languages we’d use something called structural pattern matching (which Python does support), however due to the implementation in PyMonad, we need to use the Functor’s either method:

success = divide(1.0, 2.0)

failure = divide(1.0, 0.0)

# Result: 0.5

success.either(

lambda left: print(left.__name__),

lambda right: print(right)

)

# ZeroDivisionError

failure.either(

lambda left: print(left.__name__),

lambda right: print(right)

)

The either method takes two functions, one which is called when the value is wrapped in Left, and another when the value is wrapped in Right. In both cases, we’re just printing the result to the console. This in itself is a bit sketchy because in the first post in the series I specifically said that printing was impure. However, the key thing here (as I also pointed out then), is that ultimately we’re always going to need to do some side-effecting actions (or why are we even writing code in the first place), so the question is more how we handle those actions rather than whether we handle them at all - in a subsequent post we’ll look at an alternate way to do things like this.

Composing functors with map

We’ve seen how we can drag a value kicking and screaming out of a Functor, but what happens when we want to pass a value wrapped in a Functor into a normal function? Well, one thing we could do is make all of our functions aware of the concept of a Functor and account for that in the implementation, but that seems like a lot of work. What we actually do is make use of a method that all Functors define called map (in other languages this is also called fmap). This method is really the secret sauce of a Functor and it’s the mechanism that lets us compose Functors together. To get a better idea of how map works, let’s look at the type signature of a generic implementation:

def map(self: "Functor[T]", function: Callable[[T], U]) -> "Functor[U]": ...

From the type signature we can see that map acts on a Functor of type T and takes a single argument which is a function taking a value of type T and returning a value of type U. With this function, map then returns a value of type U wrapped in a Functor.

In the context of Either, map has two branches:

- If the underlying value is wrapped in

Right, then we apply the function to the underlying value and return the result wrapped inRight. - If the underlying value is wrapped in

Left, then we do nothing and return that same underlying value wrapped inLeft.

In practice, using map would look something like this:

add_ten = lambda a: a + 10

multiply_by_two = lambda a: a * 2

cube = lambda a: a ** 3

result = (

divide(4.0, 2.0)

.map(add_ten)

.map(multiply_by_two)

.map(cube)

)

# Result: 13,824

result.either(

lambda left: print(left.__name__),

lambda right: print(f"Result: {int(right):,}")

)

This should help to sell the first criteria I spoke about in the previous post around code that’s easy to read and understand. For data engineers, this will look very similar to the style of method chaining used in Spark (which is sometimes referred to as fluent interfaces), and is very natural way to chain together a series of transformations in a more general Python context.

Hopefully you can see that there isn’t that much to Functors: they wrap values to encode some kind of behaviour to help keep our functions pure, and they give us a nice mechanism to chain results together in function composition.

Applicatives

We’ve seen then how Functors can help keep functions pure and how they provide a mechanism to compose functions with their map method. We’ve also established that on the road to understanding Monads, understanding Functors and Applicatives is fundmanetal. So before we talk about Monads, let’s talk about Applicatives.

Currying

Earlier, one of the “FP buzzwords” I mentioned was currying. As well as being a buzzword, it’s also an important technique to understand when it comes to using Applicatives. Currying is is essentially the process of taking a multi-parameter function and turning it into a chain of multiple single-parameter functions whose arguments can be applied sequentially. Why we’d want to do that will become clear soon, but let’s quickly look at an example of a curried Python function. Python itself doesn’t support currying natively but PyMonad comes with built-in support for it:

from pymonad.tools import curry

@curry(2)

def add_n(n: int, a: int) -> int:

return a + n

In the above function we’ve used curry as a decorator and specified the number of parameters to be curried (in this case, two). If what I’ve said about currying is true, then we should be able to call add_n successively, one argument at a time:

add_one = add_n(1)

# 2, 2

print(add_n(1)(1), add_one(1), sep=", ")

As promised we can directly apply arguments successively as in the first example, or we can define a new function constructed by applying only some of the arguments and then finish applying the remaining arguments later as in the second example. The concept of currying is very similar to partial application, the difference being that currying always (effectively) creates multiple functions each taking a single argument, whilst partial application can produce a function of arbitrarily many arguments depending on how many of its arguments we partially apply.

Like Functors, but not

When we used map previously, I purposely composed functions which only took one argument. This is important because, fundamentally, function composition takes the result of one function and passes that single result as the argument to the next function in the chain. So how do we compose functions when some of those functions expect to receive multiple arguments? As we just saw, currying gives us a simple way to convert multi-parameter functions into multiple functions, each with a single parameter.

When we created the curried add_n function we saw that it effectively acted like two chained functions, so in theory we should now be able to use it function composition, right? Let’s use the divide function we wrote a little earlier and see:

result = (

divide(1.0, 2.0)

.map(add_n)

# Erm...what now?

)

The above code might look stupid (and obviously doesn’t work), but this is exactly what I tried to do when first learning about FP and I was a bit stumped as to what to do next (it was also when I realised I didn’t really understand Monads). How do we pass an argument from outside of the chain into the curried function? Well, we can’t use map because if we think back to the type signature of map we know it acts on a Functor and applies a normal function to the wrapped value, returning the result wrapped in the same Functor. So what do we do?

This is where Applicatives come in. As with Functors, Applicatives define a particular method, this time called amap (think Applicative map). Let’s look at the type signature of a simple amap method:

def amap(self: "Applicative[Callable[[T], U]]", value: "Applicative[T]") -> "Applicative[U]": ...

We can see that amap acts on a function wrapped in an Applicative and takes a value wrapped in an Applicative as an argument, it then applies the wrapped function to the wrapped value and returns the result wrapped in an Applicative. How does that solve our problem? Well, Either is a Functor because it defines a map method, but it’s also an Applicative because it defines an amap method. In the context of Either, amap has two branches:

- If the underlying value is wrapped in

Right, thenamapunwraps the value, unwraps the Applicative function, applies the unwrapped function to the unwrapped value and then returns the result wrapped inRight. - If the underlying value is wrapped in

Left, thenamapdoes nothing and returns that same value wrapped inLeft.

In the previous example, we’d use amap like this:

result = (

divide(1.0, 2.0)

.map(add_n)

.amap(Right(0.5))

)

# Result: 1.0

result.either(

lambda left: print(left.__name__),

lambda right: print(f"Result: {right}")

)

As promised, we’ve been able to use amap to pass in a value from outside of the composition chain into a curried function wrapped in an Applicative. Notice that we also need to wrap the value we want to pass into the curried function in an Applicative, in this case Right(0.5) rather than just 0.5, because, by definition, amap applies a function wrapped in an Applicative to a value wrapped in an Applicative (look back at the amap type signature if it’s not clear).

As with Functors, there’s really not all that much to Applicatives (not least because most Functors are also Applicatives) - for something like Either, the differentiation between Functor and Applicative is almost academic. In practice, Either is just a useful class that let’s us keep functions pure and gives us some useful methods: one to chain together single-valued functions, and one to allow us to chain together curried, multi-parameter functions.

Monads

Whilst we’re finally ready to talk about Monads, it may unfortunately be a little anti-climactic because, as you might have guessed, you’ve been looking at a Monad all along. Throughout the post we’ve been looking at Either and how it could be used in exception handling. Initially, I told you that Either was a Functor because if defined a map method, and then that it was an Applicative because it defined an amap method - as it turns out, it’s also a Monad.

To me, this is why Monads can be so confusing. In FP, we talk about Monads like Either, but we usually neglect to mention that these Monads are also Functors and Applicatives. That always made it difficult to concretely define the behaviour of a Monad - essentially, I needed someone to define the interface that Functors, Applicatives and Monads implement for it to click. Because we always talk about these structures as Monads rather than as Functors or Applicatives, we usually talk about Monadic values and Monadic functions as well, so we say that values wrapped in a Monad are Monadic values and that functions taking non-Monadic values and returning a Monadic value are Monadic functions. It’s worth noting however that not all Monads are Functors or Applicatives; if you look at the Writer Monad implementation in PyMonad, for example, it defines a map and a bind method, but not an amap method, so it’s not an Applicative.

Wait…what’s bind?

Just like Functors and Applicatives, the special thing about a Monad is a method it defines called bind (sometimes it’s referred to as Monad bind). The type signature for a generic bind method might look something like this:

def bind(self: "Monad[T]", function: Callable[[T], "Monad[U]"]) -> "Monad[U]": ...

From the type signature you can see that bind is almost identical to map except for the fact that the function passed to bind returns a Monadic value, whereas the function passed to map returns a non-Monadic value. Where is bind useful? Well, it’s useful in any situation where we’re composing Monadic functions, for example, a chain of functions, each of which accounts for various exceptions by returning an instance of the Either Monad. We can see bind in action with a slightly altered version of the Monadic divide function we defined in a previous post:

from pymonad.either import Either, Left, Right

from pymonad.tools import curry

@curry(2)

def divide(b: float, a: float) -> Either[ZeroDivisionError, float]:

return Left(ZeroDivisionError) if b == 0 else Right(a / b)

divide_by_three = divide(3.0)

double = lambda x: 2 * x

result = (

divide(1.0, 2.0)

.map(double)

.bind(divide_by_three)

)

# Result: 1.3

result.either(

lambda left: print(left.__name__),

lambda right: print(f"Result: {round(right, 1)}")

)

Note that if we’d used a call to map instead of bind, the code would still have worked; the difference is that bind returns Right(...) whilst map returns Right(Right(...)), so in this sense, bind accounts for the use of a Monadic function by unpacking one level of wrapping for us. In languages like Scala, the equivalent of bind is implemented in a method called flatMap which hints at this flattening behaviour a bit more explicitly.

As with Functors and Applicatives, hopefully you can see that Monads aren’t really that scary when you dig into what they actually do. Hopefully, you also have a much clearer idea of how we use Monads (and Functors and Applicatives), to compose functions and escape some of the usual trappings of impurity, especially where exceptions are concerned. Obviously, the examples we’ve used have been contrived, but they demonstrate the traditional means by which to build functionality through the composition of pure functions using map, amap and bind. Ultimately, if you understand how those methods work, then you can apply that understanding to lots of other Functors, Applicatives and Monads, even if their inner workings are slightly different.

The I/O Monad

I’d be remiss if I wrote a blog about FP and neglected to mention the I/O Monad since, for better or for worse (probably worse), there’s a good chance it’ll be the first Monad you come across when you start delving into FP.

I’ve implied throughout this series that the Either Monad is a sensible choice for an I/O operation that might raise an exception, but if I were programming in Haskell (or maybe F# or Scala or some other highly functional language), then I’d probably be told I should be using the I/O Monad. I also mentioned previously that we were being a bit sketchy when we just printed straight to the console when we called the either method. Again, in functional languages, the I/O Monad would be our go-to here. We already know how Monads like Either work and that, broadly, all Monads implement similar behaviours, so how does the I/O Monad work?

IO in PyMonad has all the methods we’d expect to make it a Functor, an Applicative and a Monad, namely map, amap and bind. The way IO works is that it wraps the functionality that performs I/O and delays its execution until we call the Monad’s run method. A lot of times, the I/O Monad is described as containing the instructions to perform I/O, without actually performing it. How would we use IO in a Python program?

import os

from pymonad.io import IO, _IO

def get_env(var: str) -> _IO[str]:

return IO(lambda: os.environ[var])

def put_str_ln(line: str) -> _IO[None]:

return IO(lambda: print(line))

os.environ["LINE"] = "An example of using the I/O Monad."

result = get_env("LINE").bind(put_str_ln)

# <pymonad.io._IO object at 0x10ac7f190>

print(result)

# This is an example of using the I/O Monad in Python.

result.run()

We can see that without calling run we just return an instance of _IO and the wrapped code is never actually executed. Notice in this example that I’ve used functions like get_env and put_str_ln in the composition chain which both return an instance of _IO, why is that? The reason is that if we included something like the divide function from earlier which returns an instance of the Either Monad, then the I/O Monad’s bind method wouldn’t know how to handle the fact that divide returns Either and not _IO. We can see this explicitly if we look at the type signature of the _IO class’s bind method in the PyMonad source code:

def bind(self: "_IO[T]", function: Callable[[T], "_IO[U]]") -> "_IO[U]": ...

In languages like Haskell and Scala, the solution to this kind of problem would be to use something called a Monad transformer which allows us to stack the behaviour of different Monads and use them as though they were one. Unfortunately, PyMonad doesn’t support this feature, and this is one of the reasons I didn’t bother using IO previously. I also don’t particularly like the implementation in that IO is a function which returns an instance of the private (in the Python sense) _IO class that we’re not really supposed to use (though it’s nice that we can still sub-type it if we really want to). In addition, notice that if there was an error in get_env, then our code does nothing to handle it and our program would still blow up. This is another example of why the ability to use a Monad transformer is useful if we’re going to start using things like IO, since we could combine the functionality of IO with something like Either or Maybe.

Is there a downside to not using the I/O Monad?

It’s worth pointing out that the I/O Monad doesn’t somehow magically make our code pure (though there are plenty of arguments to the contrary). The reasoning from people who argue that the I/O Monad does make a function pure is usually along the lines that since it delays the execution of the internal function it wraps, it’s referentially transparent and itself doesn’t actually produce side-effects – every time we call the function, we always return an instance of _IO. Personally, even if that reasoning is technically correct, it feels a bit esoteric. Is my function really pure just because I stop it executing for a while? Regardless of how you skin the cat, you’ll ultimately call the run method and the instructions that were taken directly from your “pure” function will cause an impure action to occur. If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it’s probably a duck.

All the I/O Monad appearing in the type signature of a function should really tell us is that the function is definitely impure or it wouldn’t need to use the I/O Monad in the first place (there’s supposedly a quote to this effect from Martin Odersky, the creator of Scala, but I couldn’t find it). For me, this is the main benefit of using IO over something like Either since, as we saw, Either can be used for more than just I/O related actions. Given the downsides (at least in Python), however, it doesn’t seem worth the trade off when building real-world functionality.

If we really want to make it obvious from a function’s type signature that the function performs I/O whilst still being able to manage exceptions with Either then, as suggested in Functional Programming, Simplified, we can define a type alias instead:

import os

from typing import TypeAlias

from pymonad.either import Either, Left, Right

StringIO: TypeAlias = Either[KeyError, str]

def get_env(var: str) -> StringIO:

try:

return Right(os.environ[var])

except KeyError as e:

return Left(e)

In this way we achieve a few things:

- We’re able to handle and maintain information about an exception

- We make it clear in the type signature that the function is impure, and

- We’re able to more easily carry out function composition

Should we bother?

Despite the fact that I’ve talked at some length about the basics of Functors, Applicatives and Monads in Python, as well as how they fit into functional programming more broadly, there’s still a looming question - should we bother using them? To me, the fact that it’s taken this long to give what I would consider to be a sufficiently detailed explanation of how they work is quite telling. Not only that, but I only spoke about two Monads in any detail, Either and IO, but I brushed over the fact that there are all sorts of other Monads designed to tackle different problems and, whilst similar, all these Monads do work differently. As I’ve said before, I don’t think that Monads are particularly complicated in principle, but I do think they’re extremely unfamiliar to most people, especially in the context of Python.

At the start of this post, the first criterion I said I wanted my code to adhere to was that it easy to read and understand. I’ve argued that the Monadic code we wrote in previous posts fulfils this criterion. After all, remember how nice and readable our code looked when we used things like map and bind and how we could read the code like we were reading plain English? I think this was a bit misleading. Was it really the use of Monads that made our code so easy to reason about? No. We happened to use Monads to compose our functions, but it was function composition and well-named functions that made our code feel so clean. What’s more, what happens if someone needs to add new functionality to our code, say logging? Do they need to start reading all about the Writer Monad and figuring out a way to replicate a Monad transformer or start wrapping Monads in other Monads to handle exceptions when they want to log in the same function?

Monadic Python code is easy to read and understand if you understand how Monads work, but by that logic, isn’t all code easy to read and understand to someone? “Easy to read and understand” should apply to a wider audience than just the person who wrote the code and be deeper than a superficial understanding after a quick once-over. In a professional setting, you’re not the only person who needs to read, understand, maintain, and extend the code you write.

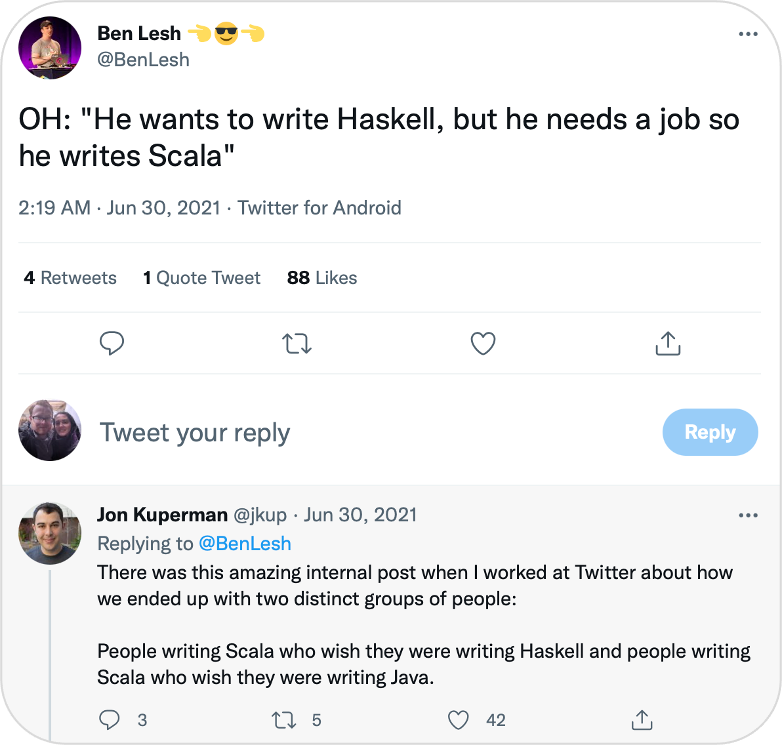

Ultimately, my biggest criticism of Monads in Python is simple: Monads aren’t Pythonic. The idea of code being Pythonic might seem a bit ideological or cultish to you, after all does it matter if our code is Pythonic if it works? I think it does. The danger we get into when we start introducing concepts like Monads into our Python code is that it very quickly stops looking and, more importantly, behaving the way someone could reasonably expect Python code to look and behave. Especially in a professional setting, that’s a problem. Imagine you’re working on a project, and you’ve made your entire codebase ultra-functional; exceptions don’t get thrown, everything is wrapped in Either and IO, you’ve written your own custom Monad transformers, all your functions are curried and so on and so forth. What happens when you roll off the project and another Python developer takes over? Well, in theory it should be fine - they write Python and you’ve written Python, except not if the Python you’ve written looks like Haskell or Scala. The point is perfectly summed up by this Tweet:

My strong feeling is that if you’re going to write your code in a way that means it ostensibly looks like Haskell (or Scala or Clojure or OCaml or F# or any other functional language you can think of), then you should just write your code in that language rather than trying to warp another language to the point of it looking alien to anyone else who develops in it. It’s precisely for this reason that the title of the blog is Pragmatic Functional Programming in Python, not Learn You a Python for Great Good. When it comes to FP, we should be pragmatic, taking the parts of the paradigm that work for us and make our code better and not worrying ourselves too much about the parts that don’t.

If you’ve gotten this far in the blog, it might feel like I’ve just told you that you should throw away everything you’ve read so far because none of it is Pythonic and you should never do it. Is that case? No. Firstly, regardless of whether you decide to use Monads, I think an understanding of them is vital when learning about FP because you’ll see them referred to everywhere, even if you don’t utilise them in your own code (plus, it’s not as if a language like Scala is alien in the data engineering space – there’s a good chance you’ll end up using it and come across Monads). Secondly, your decision to use or not use Monads should be one made based on an understanding of their pros and cons, not because you read a blog where someone told you that using Monads in Python is bad.

If I’m saying that I don’t like the Monadic approach to function composition and side-effecting in Python, what’s my alternative (and how does this all relate to testing, my second criterion)? Well, ultimately (and especially in the context of data engineering), I think the key principal to take away is the idea of building an application out of pure functions to as large a degree as possible. I mentioned it previously, but if we think about a common ETL application, we’re performing I/O operations on the boundaries to read source data and write transformed data to a target, but all the of the core business logic (the thing we should be most worried about and testing most heavily), can be constructed by sequentially applying pure functions to the original input data and it’s precisely this practice of religiously defining our transformations as pure, unit-tested functions that we can get the most value from the ideas of functional programming.

In short keep things pure and functional where you can, but don’t sweat it too much when you can’t.

tags: python - functional-programming - functors - applicatives - monads